Working for the Forest Service, I was often back and forth with leadership teams in Washington, D.C. One of those conversations revolved around a review by Elizabeth Kolbert, in the New Yorker, of Super Freakonomics published in 2009. The review starts with a parable about the projected growth curve for horseshit at the turn of the last century. Once automobiles came around, that problem dissipated – along with the rank odor of New York as the 1800s came to a stinking end.

The book’s take-home is that we just have to think about things differently and all of this stuff about the environment will take care of itself. In other words, we get more of the standard economic mantra from the same folks who brought us the collapse of 2007-2008. That new-world thinking about packaging junk loans into investments, led to old-world gifting: a $17+ trillion dollar bailout as the Fed green-washed Wall Street’s derivative sins in free money.

The horseshit-gone-away parable may be one to take to heart. The ad-hoc engineering so easily floated by the economists whose book she reviews, is much less so. We have a basic problem as humans, at least when thinking through solutions to difficult problems such as climate change. We like very straight lines and find it inconceivable that any man-made or natural system would violate that comfortable principle.

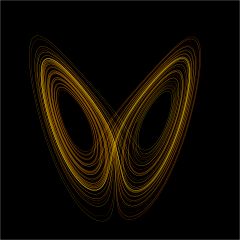

To get a feeling for what’s really going on, try figuring out when the trajectories in the image below will transition from one wing to the other.

Here’s the takeaway from that exercise: for many of us, it’s difficult if not impossible to accept two simple but profound truths:

- There are completely deterministic systems which are inherently unpredictable because their initial conditions can never be precisely stated and any imprecision – any at all – can put them on a completely different trajectory.

- The corollary is that when that path takes it onto an adjacent trajectory, it might just transition very quickly into orbiting around a very different part of the system far removed from the one it left.

So, this isn’t about straight lines. Nonlinear systems with feedback can and do behave exactly as described above. The climate is such a system. The worry is not about global warming. That might simply be a prelude. Warm the world enough to melt the Greenland ice cap – flushing all that fresh water into the North Atlantic – and you have a much bigger problem. That’s about as nonlinear as you can get on the planet and it’s happened many times in the past.

The thermohaline circulation which currently moderates the earth’s climate (we’re in an interglacial cycle within a larger glacial epoch at this point) will shut down. Without that circulation to distribute the heat that gathers at the equator, the climate will transition to another much colder state. If that happens, there’s no short-term return path to the one we’re on now. The bad news is that we have no way of predicting where we are on the current trajectory, how much we’ve done to perturb it, and whether we’ll slip onto one of those funky orbits, one that has us visiting some other system state.

Tweaking the world with giant straws to suck up the bad gases, one of the super-freaky suggestions in the book, reeks of the sort of cuteness that got us mortgage-stuffed derivatives as “investments” – and the lost jobs and sinking retirement funds that came with them.

Any system that requires a measurement unit like the Sverdrup (a million cubic meters of flow past a given point every second!) and that circulates on the order of once every thousand years (!!) is not something we should rationally be messing with. Frankly, I’d rather let the book’s authors play on Wall Street.