Just returned from a heat-seeking trip to the Southwest, one that had us at the far-edge of the ancient sea at the heart of those Western promises. Our goal was a hidden but by no means minor gem in the stunning array of National Parks, Monuments, Wildlife Refuges, and Recreation Areas, as well as the National Forests, State Parks, and other protected lands in that part of the West.

Nevada’s Valley of Fire State Park encompasses 45,000 acres of the far Southeastern part of Nevada.

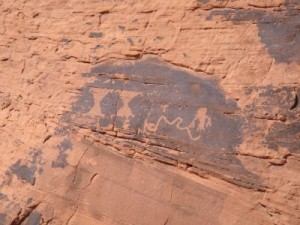

It’s off the beaten track and relatively unknown, so you have to have heard about it and want to go there to get there. The area, like much of the West, is haunted by the echoes of past civilizations, recent and not-so recent. In the park, draped over seemingly every rock where the desert varnish can be scraped away, are petroglyphs. Those echoes become very loud, incessant really, amplified as they are by the vast array of signs and symbols covering these black-red easels.

Insight into the people who wrote out this pictographic history can be gained at the Lost City Museum in Overton, Nevada. The town is located on what used to be (and will be again?) the Overton Arm of Lake Mead. I write “used to be” because the past five years have been much drier than when Hoover dam, which impounds the Colorado and backs up the reservoir, was first planned and built. The river is badly over-subscribed. That is to say there was more water promised to the Western states than can ever be delivered on a continuing basis. But that’s another story for another time. One of the reasons I left Southern Nevada was because the handwriting was on the wall. Too many people, too little water.

Speaking of handwriting on the wall, that brings me neatly back to the petroglyphs and the Lost City Museum.

Built in 1935 by the National Park Service, it’s a repository for many of the artifacts unearthed in the early part of the last century by one very dedicated archaeologist. Those were in jeopardy when it was realized that Lake Mead would eventually fill to an elevation that would flood most of them. So it did. But before that happened the Federal Government sent Mark Harrington in one more time to excavate the rest of the site.

The Museum was built to house whatever could be salvaged, along with other reminders of those who’ve come before. Included in the collection are exquisitely crafted Paiute baskets, again from the early part of the last century. My wife, who’s herself a weaver and a basket maker, was stunned at the quality.

Not surprisingly, Valley of Fire has a similar history. Originally Federal land, Nevada took ownership and established the park in 1935. Thereafter followed a real struggle to keep the park from being traded off for land closer to Las Vegas which was emerging as a gambling mecca.

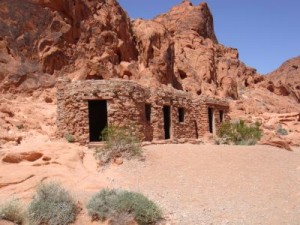

As on many other public lands in the Southwestern U.S., the impact of the Civilian Conservation Corps is readily visible. Stone cabins, originally built to house travelers passing through what was probably still wild country.

Nevada had become a state within the living memory of more than a few people at the time. It’s easier to reach these days, but I get the distinct impression that cheap travel is a tenuous gift that may not keep giving forever.