In the early 1990s, after the publication of the results from the coring of the Greenland Ice-sheet, I wrote to to express my support for inclusion of substantial tracts of inland montane forests in the Ancient Forest Protection Bill (Jontz 1992) being proposed at that time. Those cores made it clear that Earth’s climate was capable of very rapid shifts (Taylor 1999). That had serious implications for the genetic diversity of our western forests. Below is what I sent off to Congress.

I worked on air quality, water quality, soil nutrients, range management, wildlife habitat and forest dynamics with the U.S. EPA, and the U.S Forest Service in Nevada and Eastern Oregon for almost 35 years. Over that period, I developed a deep and abiding love for the island forests of the interior. With that had come a scientific interest in the development and status of the forest communities during the last few thousand years. It is from that perspective that I write this.

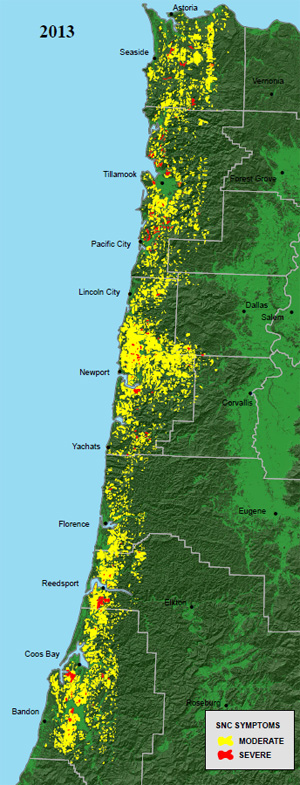

With climate modification a growing planetary concern, the interior western forests may offer us one of the best reservoirs of the genetic diversity necessary to cope with the changes which might result from such a catastrophic shift in the climate regime.

The Ponderosa Pine (Pinus Ponderosa) zone defines the boundary of almost all interior forests in the western United States. It is the most drought tolerant giant conifer forest in North America1. Paleobotanists examining the fossil record have found evidence that these forests have existed, in the past, in many different configurations. Plant associations which have no current analogs can be found in the fossil record:

Range shifts occurred that could not have been predicted … [these] apparently led to anomalous species associations” (Spaulding 1984).

The implication of these findings is of major importance for coping with changes in the variation of seasonal precipitation and temperature distribution which will result from modifications in our climate. We must assume from the fossil evidence that the gene pool of these forest types represents a large reservoir of unexpressed diversity. This diversity provides a crucial hedge against climate change, allowing the drought tolerant Ponderosa pine forests to adapt quickly to altered conditions.

In another vein, evidence of the massive failure of silvicultural theory on both public and private lands is all around us here in the Blue Mountains of Eastern Oregon. Foresters who chose to “liquidate” the stands of old-growth Ponderosa pine in favor of what they promised would be fast growing stands of Douglas-fir and Grand Fir have helped eliminate much of this gene pool.

These overstocked fir stands are now showing strains from attacks by insects and disease. In certain areas, they also constitute a serious fire hazard. This attempt at forcing these moderate to low-elevation sites to produce as if they were industrial forest plantations has been very misguided and extremely damaging. It has also served to reveal the sorry state, with some exceptions, of public and private forestry in this part of the country.

Douglas-fir and Grand fir will always be a part of these forests, and at higher elevation, they can even dominate. But at the forest margin, these trees are a minor component. Because of this, many of these stands cannot be economically managed now or for the foreseeable future. They are much more valuable for their water, forage, recreation and soil stabilization potential than as poorly managed quasi-industrial forests.

To insure the renewed health of these forests, and to protect against the looming possibility that we are in the process of forcing the world’s climate into a new state, we must protect as much of the remaining Ponderosa pine forests as possible.

Franklin, Jerry F, and C. T Dyrness. 1988. Natural Vegetation of Oregon and Washington. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press.

Jontz, Jim. 1992. H.R.842 – 102nd Congress (1991-1992): Ancient Forest Protection Act of 1991. https://www.congress.gov/bill/102nd-congress/house-bill/842.

Spaulding, W. Geoffrey. 1984. “The Last Glacial-Interglacial Climatic Cycle: Its Effects on Woodlands and Forests in the American West.” In Eight North American Forest Biology Workshop. Utah State University, Logan, UT: Dept. of Forest Resources, Utah State Univ. http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US8641645.

Taylor, Kendrick C. 1999. “Rapid Climate Change.” American Scientist, July. http://www.geo.umass.edu/courses/geo458/Readings/Taylor99_AS.pdf.

1 The Ponderosa pine of western North America is one of the worlds largest forest trees, with individual specimens reaching 4 feet in diameter, and more than 150 feet tall (Franklin and Dyrness 1988).